It’s common to hear those who speak on refugees and asylum seekers appeal to the story of Jesus’ family’s escape from the military threats of Herod’s army as a reason for identification with and compassion for the plight of refugees and other immigrants in the world today.

In its simplest terms, it is urged that “Jesus was a refugee”. But is such a statement accurate in the context of contemporary political debates?

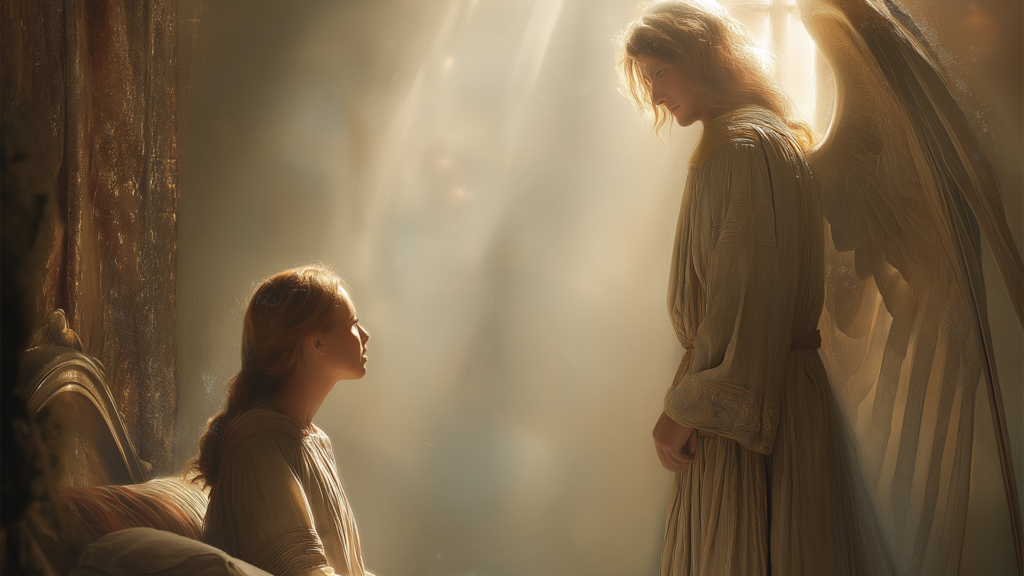

The story is told in Matthew 2. Sometime after the birth of Jesus, a group of “wise men from the east” arrived in Jerusalem, searching for “he who has been born king of the Jews” (verses 1,2).* This caught the attention of Herod the Great, the Roman-appointed king of Judea from about 34 BC to his death in about 4 BC. After consulting with these wise men and Jewish religious leaders, Herod was able to ascertain the place and time of this birth and sent soldiers to kill “all the male children in Bethlehem and in all that region who were two years old or under” (v16). However, according to the biblical narrative, Jesus’ father Joseph had been warned in a dream to escape to Egypt, so avoiding this “massacre of the innocents”. Jesus’ family remained in Egypt until the death of King Herod—likely a period of a few years—before returning to their home in Nazareth.

In terms of Article 1 of the Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (2010), it seems clear that the family of Jesus had a “well-founded fear of being persecuted” for religio-political reasons. The reason they were targeted is explicit in the story, even if these identification and claims were made about them, not by them. The violence from which they escaped demonstrated the reality of the threat against them.

The challenge of identifying the family of Jesus as refugees under the modern definition hangs on the understanding of the nation state, less recognised and less defined in the ancient world. Emma Haddad, CEO of the non-profit organisation St Mungo’s, points out that “jurisdictional boundaries in the medieval world were more porous and overlapping than the rigid, impenetrable borders of the modern world.”1 Such porous boundaries were even more so in the ancient world and under the broad reach of the Roman Empire in the first century BC. Both Judea and Egypt were merely provinces and their rulers appointed by the authority of Augustus Caesar, whose jurisdiction was acknowledged in the other biblical birth narrative of Jesus (see Luke 2:1).

By this technical definition, the claim “Jesus was a refugee” is inaccurate: “As nation-states are constructed, so the refugee is also constructed and the two concepts in some sense reinforce each other.”2 The absence of sufficiently border-defined nation states in the ancient world precludes the possibility of this designation.

However, that Jesus’ family found protection in Egypt, beyond the reach of Herod, his soldiers and his threats demonstrated a clear refugee-like experience. Daniel Carroll’s summary is more correct: “The migration of this family locates the Jesus story within a movement that spans history, of people desiring a better life or escaping the threat of death”.3 While not as pithy, this should illicit no less empathy and compassion from those who claim this story of faith as formative for their lives and public engagement. As Jesus would put it later in His life, identifying with these are so many other human experiences: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me” (Matthew 25:35).

Or not (see Matthew 25:43–45).

*Bible quotations from the English Standard Version.

1. Emma Haddad (2003), “The Refugee: The Individual between Sovereigns,” Global Society 17(3), page 302.

2. ibid, page 299.

3. Daniel Carroll (2013), Christians at the Border: Immigration, the Church and the Bible (2nd edition), Brazos Press, page 106.

Nathan Brown is the book editor at Signs Publishing.