The immediate post-war years continued to see stories and experiences of the war shared in the pages of Record. Missionaries continued to return to their homes in the Pacific Islands, with both joyful reunions and sorrow as they learnt the fate of many of their local friends during the war. Adventists in Europe were struggling with a lack of food, so many Australians and New Zealanders were sending food parcels to families who were very grateful to receive a variety of food (as their rations were basic and minimal).

In the first publication for 1947 (vol 51 no 1) of the Australasian Record, Gordon Turner, the Australasian Union Conference president, described the post-war years:

“The year 1946 has been a period of adjustment for many, and now after six years of war more normal conditions prevail. . . The new year, 1947, will be a somewhat settling-down period. To those who recognise the imminence of our Lord’s return, it must be another and a greater opportunity for service for God. Time is fleeting.”

In the next issue (vol 51 no 2), Pastor Kata Ragoso, who was left in charge of the Seventh-day Adventist work in the Solomon Islands when all expatriate personnel returned to their homelands at the beginning of the war, shared his wartime experiences. Titled “How 214 Soldiers and Airmen were Saved from Death in the Solomons”, the dedication of this Adventist leader is inspirational.

“After the missionaries were evacuated from the Solomons, I called a hundred of my people together to build storehouses in the bush, to hide the missionaries’ goods and the equipment from the Batuna hospital and school. We carried timber and iron three miles out and built two houses, and then packed all the goods and marked the boxes with the initials of the owners, and carried them into the bush. The furniture we placed in the house with the leaf roof, and the other things we placed in the store with the iron roof. Next we took the two boats, ’Vinaritoke’ and the ’Portal’, and with a big canoe towed them up a river. We took down the masts and laid them on the decks. Then we built a leaf house over the boats so the aeroplanes could not see them.

“After that we put watchmen every five miles from Gatokai to Vella Lavelle, to watch for planes and warships. When any plane was shot down the watchmen reported it to me and I sent some men out to find it. When we found any airmen we took them to our villages and mission stations and looked after them until we could take them to the wireless men (commandos). We had no white people’s food, but we gave them the native food. Sometimes we took them to the wireless men at night, through the Japanese lines. Sometimes we took them in the day; and when the aeroplanes came over we made the white people lie down in the canoe and we covered them with leaves. When we reached the wireless men they would send a message to Guadalcanal or [Vanuatu]; then an aeroplane would come and take the airmen away.

Altogether we rescued twenty-seven American pilots and one hundred and eighty-seven Australian and New Zealand soldiers. The 187 men were on a warship which was torpedoed by the enemy. When it sank these men started to swim, but they would never have reached shore. Our men went out in their canoes and brought the soldiers to land. It took a lot of food to feed them, but we did not keep them very long. The wireless men sent a message and a big warship came and took the soldiers aboard.

Each Afraid of the Other

One Sabbath when we came out from the service two planes were fighting overhead. After a while the Japanese shot the American plane and it fell down into the water. I sent some of my men out in a canoe to find the pilot. Late in the afternoon all except one returned and said they could not find the pilot. When the plane sank the airman got into his rubber dinghy and went ashore on one of the islands and stayed there that night. One of my men, Tiri stayed there searching for the airman.

Early next morning he saw the American come out from the island in his dinghy, so he paddled after the man in his canoe. When the pilot saw Tiri he was very frightened. He thought the black man would kill him. Tiri was frightened too; he thought the airman might be a Japanese. But when he came close the airman smiled, and Tiri spoke to him in pidgin English: ’Are you American or Japanese?’ The answer came, ’I am not a Jap; I am an American. Where do you come from?’ ’I belong to the mission station’, Tiri called to him. When the airman heard this he was very happy. He beckoned with his hand and shouted, “Come close to me!” So Tiri went and put the injured man into his canoe and towed the dinghy behind. He paddled hard and came to Batuna.

I went down to the wharf and said to Tiri, ’Why have you brought this Japanese here? We will attend to them at some other place’. Tiri replied, ’He is not a Japanese; he is an American’. So I went down and looked carefully into his eyes and asked him if he was a real American. Then I asked him, ’Which part of the United States are you from?’ He said, ’I come from Hollywood, California’. So I told him I had been to Hollywood and was very pleased to see him. I asked him to come up to Pastor Barrett’s house. We gave him oranges, papaws, and coconut juice and cooked some sweet potatoes. We gave him a shower, then I asked the dresser who looked after the hospital to give him some medicine and bandage the man’s arm and leg. Twenty-one men in a canoe took him to the wireless station, and later an American plane came and took him away. After he went back to America he wrote a letter of thanks to me and my people.”

In this same issue, a letter from Alma Wiles who was working as a nurse in Papua New Guinea, was published. Titled “Snake-bite Victim Saved by Missionaries’ Strenuous Efforts and Prayer”, she makes a humorous comment in the retelling of how a young PNG boy was saved from a snake bite:

“The boy was blind, could not speak, could not swallow, and was choking with mucus which the paralysed muscles of the throat could not cough up. My first thought was for something eliminative and something stimulating. We gave him an enema and then poured strong coffee down his throat—I had heard that tea and coffee are a partial antidote for snake-bite, so begged some from Mr. Miller on our way back. But the joke came when out of the six of us white folk no-one knew how to make coffee!”

In 1950, the Australasian Inter-Union Conference held a session, which was the first since the unions were reformed in 1949. Andrew Dawson, the manager of the Australasian Conference Asssociation (which held the real and intellectual property of the Church), summarised the Church’s financial status as follows (vol 54 no 49):

“The immediate post-war years covered by this report have not been without their problems. We have witnessed a change from a seller’s to a buyer’s market, a spiralling of costs, an acute shortage of labour, stringent price controls for many years, and other items too numerous to mention. But through them all we have witnessed the kindly, guiding hand of a heavenly Father whose help and counsel have been constantly sought. For His help we want to express our grateful thanks, and in the light of His past blessings we look forward to the future with confidence, knowing that with Him there is no crisis, and all things are possible.”

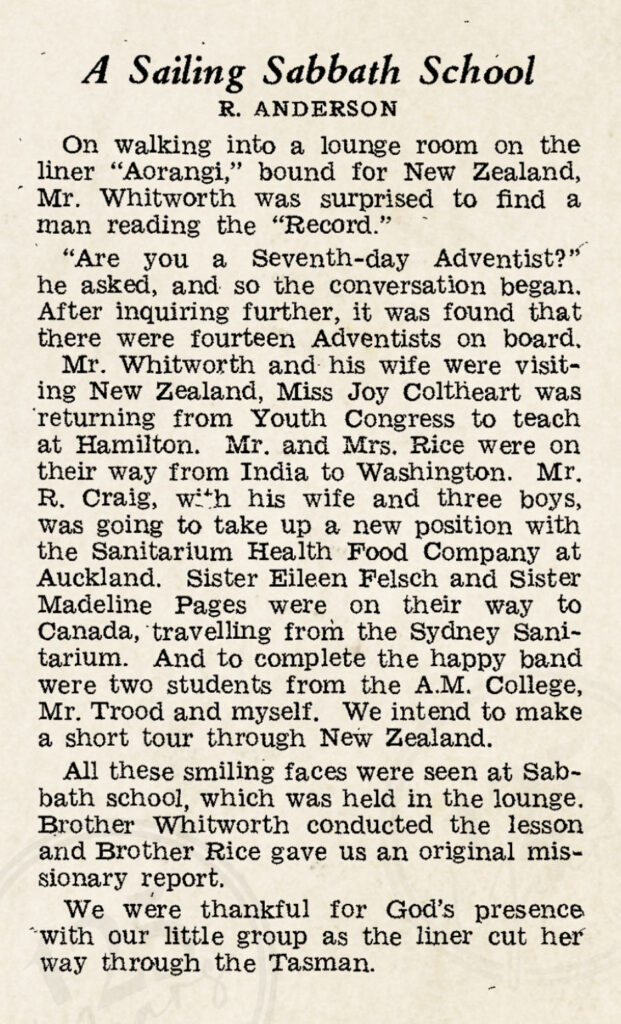

This excerpt (left) from February 1950 (vol 54 no 9) tells of how a group of Adventists found each other on a boat from Australia to New Zealand—all because of Record!