As-salatu khayrum minan-naum.

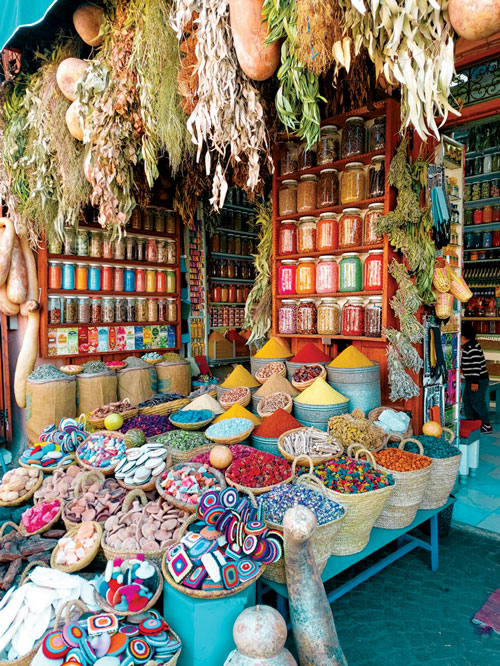

This is what I wake to at 4:30am from my riad in Marrakech, Morocco. My dad sleeps through it and I hear my mum roll over in bed, signalling it’s woken her too but that she’s adamant about getting a few more hours of sleep.

As-salatu khayrum minan-naum.

Footsteps scurry around the hallways of the riad, across the cold tiles and out the brass door at the entrance. I’m guessing it’s not other travellers, but local workers responding to the heavily amplified prayer call, also known as the adhan. Even this early in the morning, it is loud, but still melodious. The notes trail and dip and whisper at the end of each line before the vocalist reaches for another breath.

As-salatu khayrum minan-naum.

My parents and I have been travelling through Morocco for a few weeks now, to the point that I can tell that this call is different from the rest. This one repeats the same five words over and over, for the next 10 to 15 minutes. On a six-hour train trip to Fez later that morning, I’m told by a local lady on her long commute to work, that it’s the pre-dawn prayer.

As-salatu khayrum minan-naum translates to prayer is better than sleep.

If you’ve ever been to a Muslim country, you’ll no doubt be able to transport yourself back to a time you heard the adhan echo over the city. In countries like Morocco, Turkey, Egypt and Iran, it’s broadcast five times a day through loudspeakers that extend from minarets at the top of mosques. There’s a designated spot for the muezzin (the person responsible for calling Muslims to prayer) to recite the call in all directions.

Because the adhan is based on the lunar calendar, the times it starts change slightly each day, depending on the sun’s position in the sky. The first call is when the appearance of light can be seen on the horizon. The second is when the sun begins to descend after reaching its highest point in the sky. The third is when the sun reaches the midpoint of its descent. The fourth is just after sunset, and the fifth is when the sun’s light disappears from the sky and darkness has set in.1

The typically husky and imperfect voice of the muezzin crackles through speakers across the city. If you stop and listen, you can hear the adhan coming from various other nearby mosques. Sometimes, it sounds like the muezzins are yelling out to each other, singing in rounds or competing over who can call the loudest. And it is . . . consistently loud. Throughout the day, it overrides honking motorcycles, conversation and the cacophony of market barterers in the medina. Some hotels and hostels even offer a price reduction simply for being next to or near a mosque.

Allahu akbar. La ilah ill Allah.

God is the greatest. There is no god but Allah.

While I know of travellers who have embraced the prayer calls and stopped to take in the shift of movement in the city when they occur, others find them annoying and are quick to block their ears.

A young Moroccan girl who guided me through the tanneries, that smelt of animal skin and stagnant water, said many locals respond to the calls and go to the mosques to get right with God or meet societal expectations. Others treat it like a duty that needs to be ticked off. “It’s part of the culture,” she explained. “It’s what everyone does.”

Soon after, I read from Idris Tawfiq in Arab News another perspective. He said, “The five daily prayers are a way of giving meaning to our lives and of setting aside just a few minutes each day to return thanks for all we have . . .

Being faithful to the five daily prayers changes us for the better. Better than watching TV, better than chatting on the internet. . . What’s more, regular prayer makes us better people, better Muslims, since its effects stay with us for the rest of the day.”2

This tension lies in most spiritual practices. Many look at the things we do—the Sabbath, what we do or don’t eat, our daily devotions, fasting—as unnecessary, legalistic, outdated and cult-ish.

From an Adventist point of view, I think the things that set us apart are good and I stand for them. However, I can understand why my friend, who has recently started attending church, has been given warnings when she’s told other Christians she’s been attending an Adventist church. I get why people have told her, “Be careful, they have a lot of rules”, and “I hear if you don’t follow what they believe, they’ll kick you out”, and “Hmm, they’re like the Pharisees”.

There are many practices that, at their core, are beautiful. But if we do them with the wrong heart or mind, and are judgemental towards others, our actions can become dutiful in nature and unattractive in appearance.

Let’s take the Sabbath. While some keep it with intention week in and week out, for many it’s become a normality—something they do, just because. Others practice it like it’s a duty; to get right or stay right with God; or because it’s expected of them by friends, family or peers. But we can follow all the basic guidelines of attending church and abstaining from work and still miss the point entirely. As John Mark Comer said in Practicing the Way, “Previous generations often thought of the Sabbath as a sombre, serious day full of religious duty and legalistic rules. Today, many people think of it as a day to chill, relax or sleep. Both generations miss the essential truth—the Sabbath is designed by God as a day to give yourself fully to delight in God’s world, in your life in it, and ultimately in God Himself.”

The end goal in all our practices is not to pray X number of times a day, have a perfect record of well-kept Sabbaths, or be able to boast about our soberness or meat-free meals. The end goal in all these things is to grow closer to God and become a person who is marked by a spirit of rest. Who is generous, forgiving, wise and, most of all, loving. If our practices are making us prouder, more judgemental, hurried, harsh or anxious, we’re likely missing the point.

Of all the things I’ve experienced in my travels, the adhan is one of the things I wish I could put in my duffle bag and bring home. Imagine if there was a public prompt that rang over your city five times a day to remind you to step aside from everything that diverts your attention and turn to God. Endless opportunities to be grateful; to plead for justice and an end to violence; for priorities that value freedom and peace. While there are those in Muslim countries like Idris Tawfiq who remind themselves of these things, there are likely many others who groan at the sound of the calls, bow their heads with busy minds and walk away unchanged.

If we want to experience God’s goodness in more profound ways and if we want others to see the beauty in our practices and our God, we must remind ourselves why we do what we do, often.

It’s easy to lose sight of the reason for the things we do when we do them so regularly. Grace is given there. But, let this be an invitation to look at the things you do in the name of God. Have your practices become habitual? Are they transforming you into someone who is more like Jesus? Are you ticking things off like a checklist or doing them to meet expectations? Or are you dragging your feet to the mosque and leaving onlookers shrugging?

Zanita Fletcher is an assistant editor for Signs of the Times.