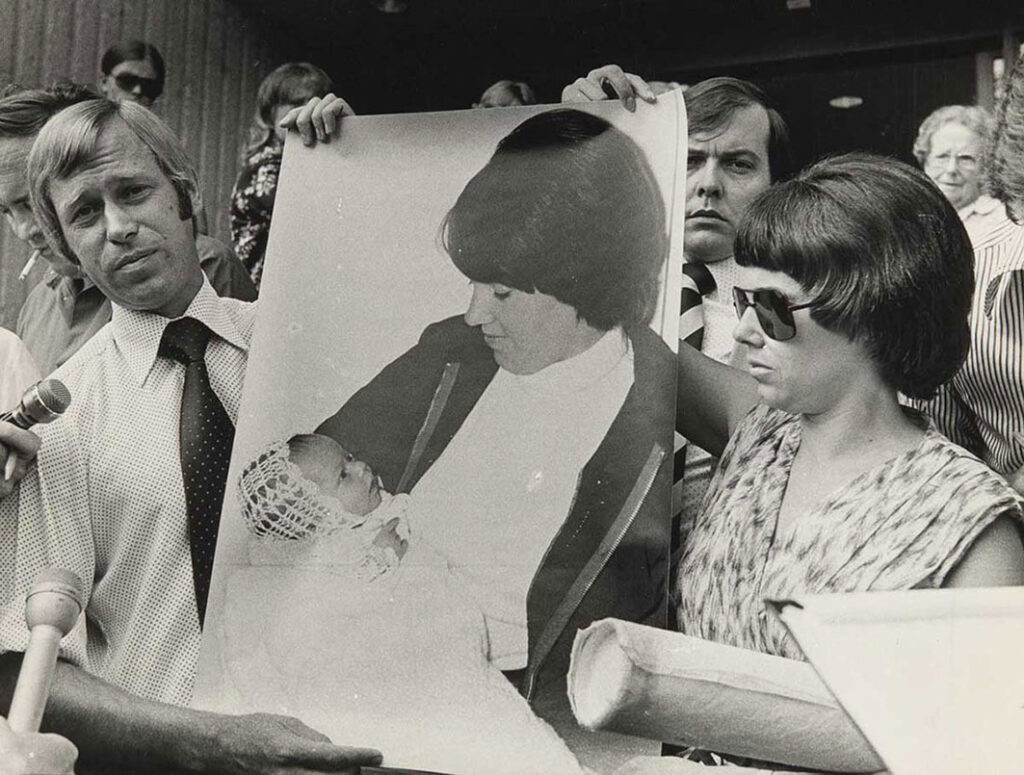

One of the biggest cases to have ever challenged the public’s trust in the justice system of Australia is the case of Seventh-day Adventist mother Lindy Chamberlain. It was a case which would go down in legal records as “the case of the century” (Adventist Record, July 23, 1983).

Without any evidence of a weapon, a motive, the child’s body, a witness, a confession of guilt, or any tangible condemning evidence, Lindy Chamberlain was charged and convicted for the murder of her eight-week-old child, Azaria, on October 29, 1982. Upon appeal to the Federal Court in 1983, and later the High Court in 1984, Lindy Chamberlain’s appeals were rejected, and her life-sentence for murder maintained. Her husband, Michael Chamberlain, was a pastor of the Seventh-day Adventist Church at the time and was convicted of being an accessory after the fact and was given an 18-month suspended sentence.

Shockwaves of disbelief and incredulity reverberated across Australia and the Adventist Church when the finding of guilt was announced, with many people refusing to accept the guilty charges against Lindy to be true. More than 131,000 signatures were gained in a petition demanding a full judicial inquiry into the Chamberlain case and the immediate release of Lindy Chamberlain (The Canberra Times, May 4, 1984). The organiser of this petition, Guy Boyd, viewed this case as a threat to the judicial system in Australia, and “the worst case in Australia’s judicial history—without the slightest doubt” (Record, October 15, 1983).

In principle, the Australian justice systems maintains the presumption of innocence. This requires that the accused individual is to be considered and treated as innocent until the prosecution proves “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the individual was responsible for the crime. But in the circumstances of Lindy Chamberlain’s case, this principle was simply ignored. “It is incomprehensible that a person could be convicted of murder without a motive having been established and without the question being settled as to how, when, and where the body could have been disposed of. By no stretch of the imagination can it be said that the verdict was ‘beyond all reasonable doubt’” (Record, November 27, 1982).

Every detail of evidence which pointed towards Lindy’s innocence was taken by the prosecution to instead be evidence of guilt. How could the justice system get it so wrong? How could they look at the evidence (or lack thereof) before them and accuse Lindy of the heinous crime of murdering her own child? Australian author and lawyer, John Bryson, pointed out the extent of the court’s failings by observing that, “This was not the first time a prosecution was successful without the production of a body, or without a weapon, or without eyewitnesses, or without proving a motive. But here the prosecution was without every one of those evidentiary advantages” (Record, July 23, 1983). The justice system failed Lindy Chamberlain that day, and a great miscarriage of justice was witnessed by the whole Australian population.

The Chamberlain case not only challenged the efficacy of the Australian judicial system, but it also put the beliefs of the Adventist Church in Australia under great scrutiny. Few Australians during this time had any knowledge of the doctrines and practices of the Adventist Church, and rumours ran rife. Some of the opinions and rumours which were spread included that child sacrifice was part of Adventist doctrine, that Adventist couples did not desire children and that clairvoyants were more trustworthy than Adventist ministers. Cynicism towards Christianity grew exponentially in the eyes of the public. After all, the testimony of a pastor, Michael Chamberlain, was discredited by the court and considered unreliable (Stuart Tipple, “Chamberlain legal case”, Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists).

In response to this widespread cynicism, the Church maintained a conservatively neutral but consistently supportive position towards the Chamberlains and attempted to dispel these rumours by encouraging church members to show the world their compassion. “Whatever other factors may be involved, through this tragic circumstance God is giving His church the opportunity to show the world that the Adventist family has compassion” (Record, July 30, 1983).

The Church wasn’t without its critics, however, for not taking a more active stance in the case. A significant proportion of Adventists held the view that the Church should have been more active in supporting the Chamberlains by advocating for a judicial inquiry into the case (Record, April 13, 1985). Yet because of the Church’s calm response, the Seventh-day Adventist Church was held in high esteem by prominent legal experts for its conduct towards the case: “‘You have consistently upheld law and order, you operate according to Christian principles and don’t overreact to trying circumstances’” (Record, December 24, 1983). Maintaining this calm response provided an assurance to the Chamberlains that hope was not all lost.

As well as the horrific loss of her child, Lindy endured accusations and demonisation from the media, becoming the most hated woman in Australia, as well as separation from her family, and the seemingly hopeless situation of no clear legal recourse beyond the High Court’s rejection of appeal. Yet throughout all of this, Lindy relied wholeheartedly on God. She refused to let the trials and hardships overcome her. Like Joseph in the Bible who endured false imprisonment, Lindy remained steadfast in her faith. She remained kind, considerate and loving and was “more concerned about the welfare of others than her own plight” (Record, November 19, 1983). According to the warden of the Berrimah jail, Lindy was “always gentle and understanding” and had “won the hearts of everybody in this place” (Record, November 19, 1983). Many of the staff and prisoners at Darwin’s Berrimah jail did not believe Lindy killed her eight-week-old baby, with one prisoner saying, “She did not kill that baby . . . and we all know it” (Record, November 19, 1983).

Lindy served three years in prison before being released on the discovery of new evidence, and in September 1988 both her and her husband were acquitted, and the convictions overturned.

Throughout all this, Lindy was able to draw upon God to endure the incomprehensible hardships she faced. Today she is an author and inspirational speaker, sharing on topics like forgiveness, how to deal with stress and grief, the responsibilities of lawyers and the media to maintain the truth, and finding faith in hard times. If there is one thing we can take away from Lindy’s story, may it be the dependability of God to give hope, strength and comfort throughout every trial we face.

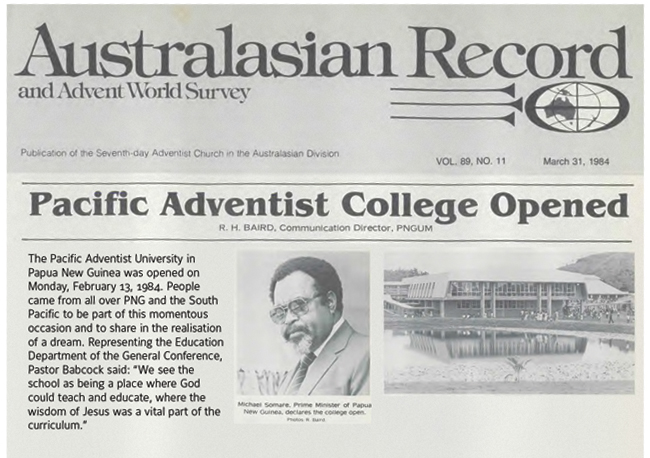

1984: Pacific Adventist University opened

The Pacific Adventist University in Papua New Guinea was opened on Monday, February 13, 1984. People came from all over PNG and the South Pacific to be part of this momentous occasion and to share in the realisation of a dream. Representing the Education Department of the General Conference, Pastor Babcock said: “We see the school as being a place where God could teach and educate, where the wisdom of Jesus was a vital part of the curriculum.”