The Seventh-day Adventist Church faced challenging issues during the 20th century concerning life in a progressively changing world. Rapid developments in industrialisation, urbanisation, immigration and cities’ exponential growth heightened the presence of injustice caused by “indifference to human suffering”.1

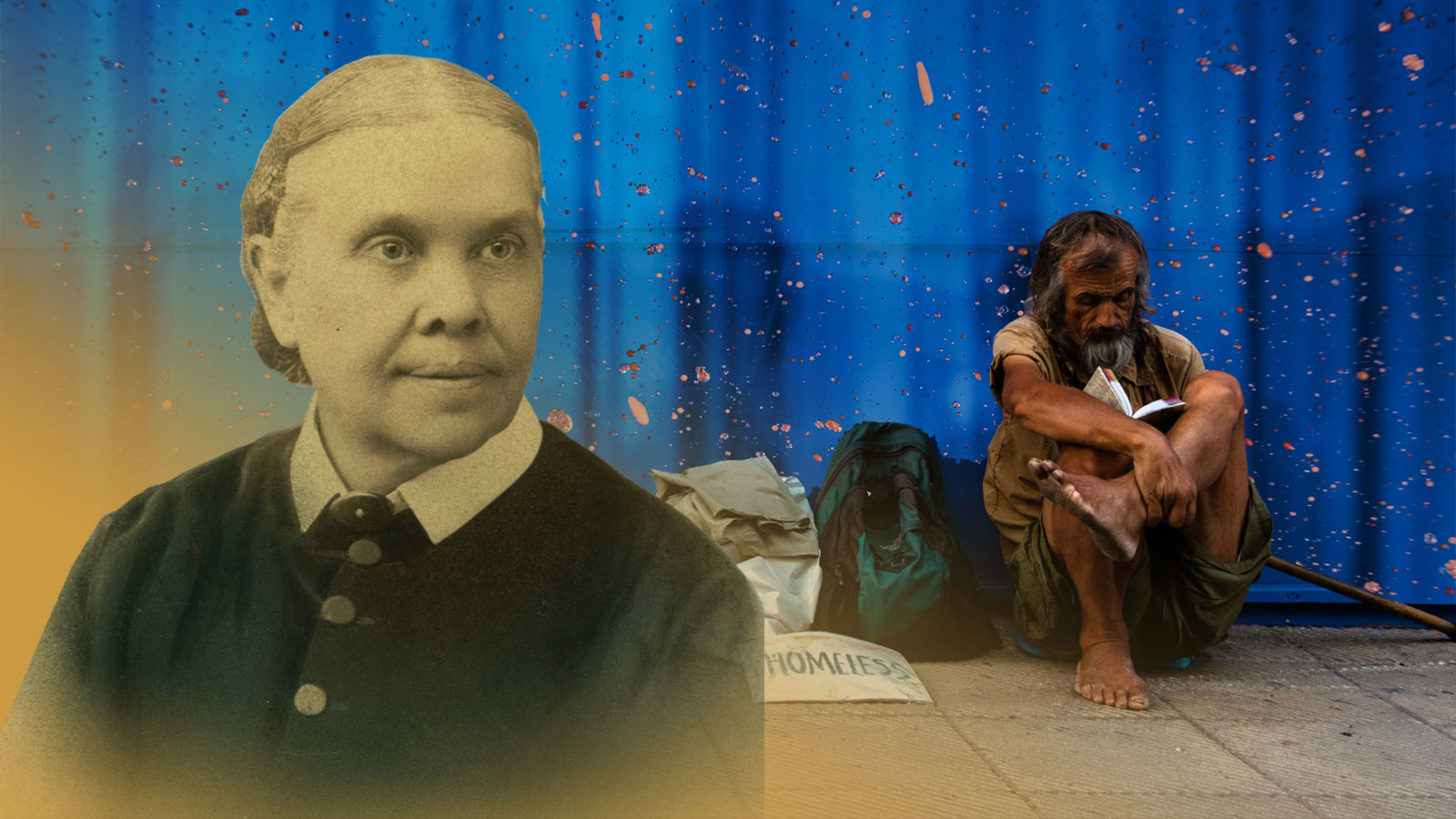

Internal denominational disputes, engendered by theological and organisational conflicts, diverted the Church’s attention from its primary mission in the world. Morgan argues that in the context of general societal issues, “Ellen White guided Adventists’ responses to the nation’s social problems.”2 Consequently, her counsels drew attention to social justice as an intrinsic part of the movement’s missional activity.

This brief reflection refrains from discussing White’s understanding and response to all aspects of social justice through the selective use of quotations, but rather aims to recapture the inspirationally nurturing and visionary depth of her inspired voice from the trenches of her lived experience.

In a letter penned to Elder OA Olsen in January 1905 (Letter 55), White described her visit to Battle Creek, Michigan. These recollections are fascinating for two reasons. First, because they delineate her role as God’s messenger. Second, she was asked whether the views she held years ago changed.

In response, she affirmed her beliefs’ unchanged continuity, but placed them in the context of the “same service” that the Master placed on her in the early years. One wonders what she meant by the continuity of her “unchanged views” and “same service”.

White’s progressive understanding of the biblical truth matured.3 She encouraged the Church to immerse life experience in the power of God’s Word to “discern more clearly the compassion and love of God” revealed in “Christ and Him crucified”,4 a place where one finds “mercy, tenderness, and forgiveness, blended with equity and justice”.5 She argued that “we should not only know the truth, but we should practice the truth as it is in Jesus”.6 This focus remained an unaltered mandate of her entire ministry—truth in terms of its practical application in the “Lord’s service”.7

In this context, she recalled her calling’s specific nature: “I was charged not to neglect or pass by those who were being wronged . . . I am to reprove the oppressor and plead for justice. I am to present the necessity of maintaining justice and equity in all our institutions.”7[pullquote]

Space does not permit a detailed analysis of White’s response to the wide range of social justice issues, both with the community of faith and in society at large, but her influence commenced at the ground level of practical responses to human needs. Soon after her marriage in 1846, God instructed her to show a particular interest in motherless and fatherless children.7 She understood this responsibility as part of God’s missional response to human suffering (Isaiah 58: 6,7) with a specific goal: “I have taken children from three to five years of age and have educated them and trained them for responsible positions.”7

During White’s tenure in Australia, her home, Sunnyside, in Cooranbong, NSW, became “an asylum for the poor and afflicted”.8 Her concern for the sick and suffering “won confidence of the people”.9 Thomas Russell, a local businessman, summarised her influence’s impact: “Mrs White’s presence in our village will be greatly missed. The widow and the orphan found in her a helper. She sheltered, clothed, and fed those in need, and where gloom was cast, her presence brought sunshine.”10 In her life and practice, the truth in Jesus translated into practical Christian experience, a place where people felt kindness and loving care.

The great controversy theme (1858-1888) contributed to White’s in-depth understanding of God’s love and His purpose for life in a broken world. It highlighted the value of freedom of choice and the intrinsic value and potential in human life. The named theme extended her ministry’s impact beyond the boundaries of the Adventist community into the “public arena—race relations and religious liberty”.11 During her time in Australia, she wrote extensively on issues relating to coloured races.12 In 1891, she wrote, “The Lord Jesus came to our world to save men and women of all nationalities. He died just as much for the coloured people as for the white race. Jesus came to shed light over the whole world.”13 Her words reflected a fearless but deeply-seeded spiritual conviction streaming from her view of Jesus’ ministry: “I know that that which I now speak will bring me into conflict. This I do not covet, for the conflict has seemed to be continuous of late years; but I do not mean to live a coward or die a coward, leaving my work undone. I must follow in my Master’s footsteps. It has become fashionable to look down upon the poor, and upon the coloured race in particular. But Jesus, the Master, was poor, and He sympathises with the poor, the discarded, the oppressed, and declares that every insult shown to them is as if shown to Himself. I am more and more surprised as I see those who claim to be children of God possessing so little of the sympathy, tenderness, and love which actuated Christ. Would that every church, north and south, were imbued with the spirit of our Lord’s teaching.”14

In 1896, she cautioned the Church: “The walls of sectarianism and caste and race will fall down when the true missionary spirit enters the hearts of men. Prejudice is melted away by the love of God.”15 Her appeals aimed to resonate beyond the realm of political activism. More precisely, she aimed to challenge the Church with a “new initiative to reach the nation’s impoverished and oppressed black population”.16 Consequently, her messages were inspirationally motivational and missional.

The example of her unique response to the ills of social injustice emerged from her sensitive approach to the abuses and mistreatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia. While writing extensively about equality, she never made a direct reference to the country’s racial prejudice. Nonetheless, her voice motivated the Seventh-day Adventist Church to speak out against this social evil. After her departure to America, The Bible Echo (August 19, 1901) published an editorial expressing the Church’s protest against government abuses and mistreatment of the Indigenous people: “Every opportunity should be improved to create a public sentiment against the brutal customs above described until the authorities take hold of the matter and inaugurate a vigorous reform. The blot is a foul upon the country, and should be eradicated without delay.”17

Indeed, her counsel challenged Seventh-day Adventists to speak out against oppression and injustice, not merely as a forum for political activism, but as an intrinsic part of the movement’s missional activity to uplift and restore human value and dignity streaming from God’s kingdom of grace.

Dr John Skrzypaszek is the recently retired director of the Ellen G White/Adventist Research Centre at Avondale University College, NSW.