Introduction

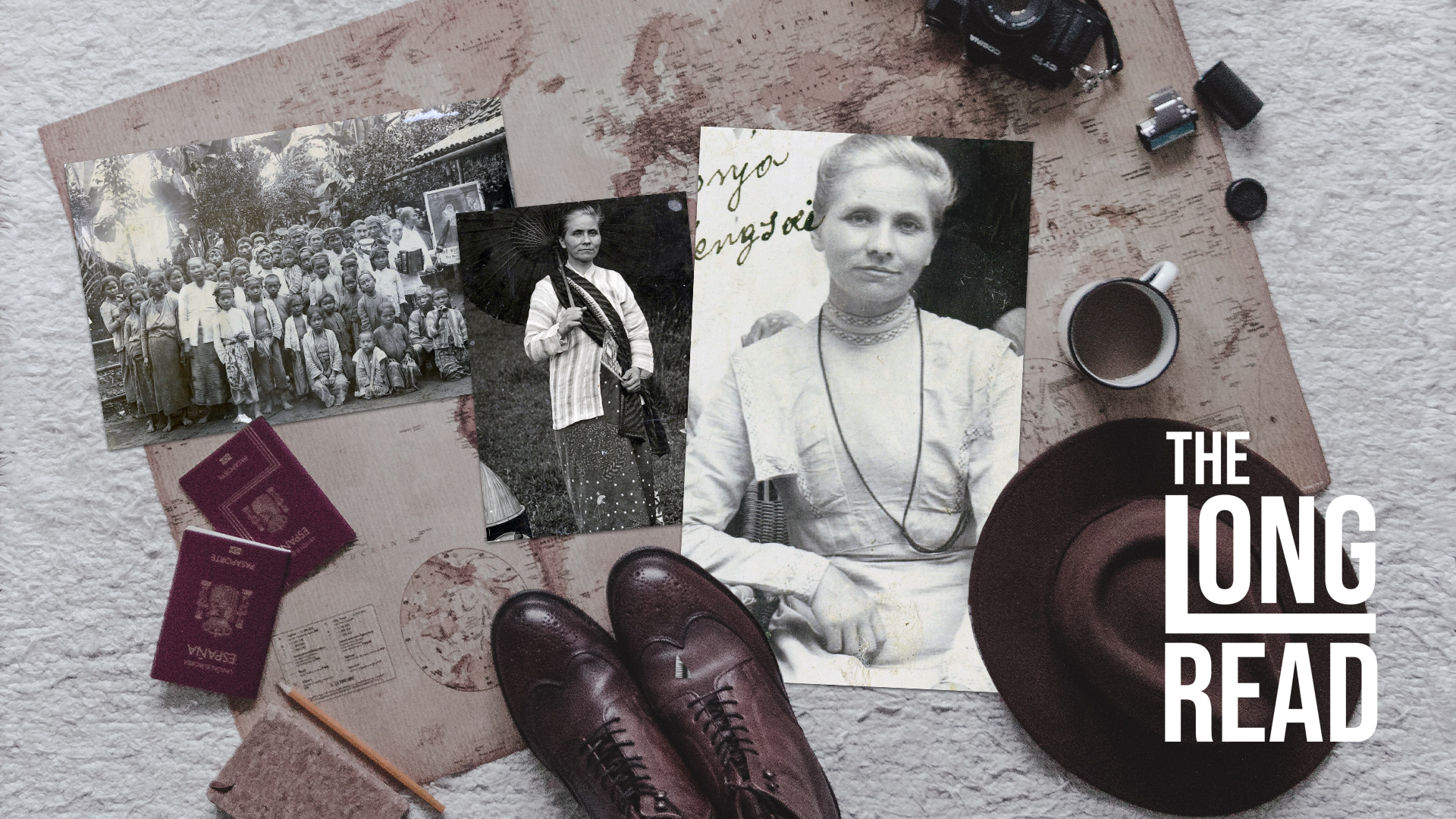

Seventh-day Adventist History is certainly fascinating. It is full of wonderful stories of faith, inspiration, and missionary efforts. Although our pioneers did not always feel the need to write their stories, the passage of time demanded the writing and publication of books in order to preserve the history of the church. Unfortunately, many of those books overlooked the participation of women in church and missionary leadership. Few authors have attempted to tell and publish the stories of those women who played influential and significant roles in Adventist history. Perhaps the pioneer in this regard was Ava Covington, with her book They Also Served: Stories of Pioneer Women of the Adventist Movement published in 1940.[i] She was followed by John Beach, with his book Notable Women of Spirit: The Historical Role of Women in the Seventh-day Adventist Church published in 1976.[ii]

Over time other researchers have explored the rich history of women pioneers, including Bert Haloviak,[iii] Michael Bernoi,[iv] Bertha Dasher,[v] Ramona Perez-Greek[vi] and Silvia Scholtus.[vii] Nevertheless, the participation of women in pastoral ministry in particular, has not always been addressed or explored. Perhaps the most important contribution to this topic was produced by Josephine Benton in her book Called by God: Stories of Seventh-day Adventist Women Ministers published in 1990.[viii] She told in detail the stories of seven women who worked as pastors and evangelists in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Other researchers that have explored this issue in-depth are Daniel Mora[ix] and Randal Wisbey.[x]

Thanks to the dedicated work of these authors and historians, today we have a much more complete history of the active participation of women in the origin and development of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. However, there is still an aspect of female participation in the ecclesiastical leadership that has not yet been properly explored, specifically the presidency of Conferences.

To this date, only one historical work has mentioned the role of women as presidents of Conferences. Historian Kit Watts, in a chapter published as part of the book A Woman’s Place: Seventh-day Adventist Women in Church and Society,[xi] mentioned that Flora Plummer was president of the Iowa Conference in 1900. She was described as “the only known case of a woman to hold such a position”.[xii] Later books and papers echoed this statement, but without exploring in more depth the history of women as conference presidents. The present article endeavors to fill this gap in the historical study of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

But before we go to the story of Flora Plummer and the other women who were presidents, we must explain briefly what exactly a “Conference” is.

What is a conference?

The Seventh-day Adventist Church emerged in the United States in the mid-19th century as the result of the Second Great Awakening and the preaching of William Miller. In their beginnings, their members were united by a series of theological beliefs in common, such as the imminence of the Second Coming, the conditional immortality of the soul, the observance of the Sabbath day, and the existence of a heavenly sanctuary where a pre-advent judgment takes place. These doctrines, or landmarks, formed the theological core that shaped the Adventist message. The need to preach these distinctive beliefs exposed the need for ecclesiastical organisation to guarantee order and efficiency in missionary activities. Despite some initial reluctance, in 1861 different Adventist congregations began to unite into “conferences”. These entities brought together different churches in the same geographic region in order to organize and coordinate their ecclesiastical and missionary activities.[xiii]

Over time the conference became the first supra-congregational administrative level of the worldwide organisation of the Adventist Church.[xiv] Under its umbrella are found all the congregations from a specific geographical area. Its responsibilities include the organisation of various ecclesiastical and missionary activities, the care of dozens of churches, and the coordination of a team of pastors and workers. A conference president heads the organisation and oversees its activities.

With this concise understanding of the formation of local conferences, we will move on to the stories of the women who served as presidents of conferences.

Flora Plummer: President of the Iowa Conference (1900)

Lorena Florence Fait was born on April 27, 1862, at a small farm in the state of Indiana.[xv] Lorena Florence, or Flora as her family called her, grew up to be a joyful young lady. As a teenager, she accepted Christ after listening to an itinerant preacher and joined the Campbellite Church. She wanted to be baptised, but it was winter and the river was covered with a thick layer of ice. But Flora did not care about the cold; she wanted to give her heart to Christ through baptism. The ice was cut and she was baptised.

A few months later Flora decided to fulfill her childhood dream and become a teacher. Consequently, she traveled to the neighbouring city of Portland where she passed the exam and received the highest certification from the county supervisor. For eight years she worked as a country school teacher, until she received a call to work in the city of Nevada, Iowa. There she met Frank E Plummer, the principal of that school, whom she married on July 12, 1883.

Two years later the happy couple moved to the city of Des Moines to work at the school there. An Adventist Bible worker offered Bible studies to the Plummers. The following year, in 1886, Flora Plummer accepted the truth of the Sabbath and joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Arthur Daniells, who later would become president of the General Conference, visited the city in that same year and described her as “a natural teacher” who “showed much talent”. Daniells was hoping that “she will yet aid us much in the work in this city”.[xvi]

During the following years, she actively participated in the missionary activities of the church including giving Bible studies and sending evangelistic literature by mail. Her skills and enthusiasm caught the attention of Iowa Conference leaders, who invited her to join the Iowa Sabbath School Association. At that time, the Sabbath School department functioned as a parallel but autonomous organisation to the Adventist Church.

Flora devoted herself body and soul to her new task, spending a great deal of time visiting homes, churches, and congregations, and writing articles and letters. She also visited camp meetings, where she held children’s meetings, sold denominational books and played the organ during worship services.

Her efforts and dedication to work made her stand out quickly. In 1891 she was named president of the Iowa Sabbath School Association.[xvii] In 1892 she was granted a ministerial license[xviii] and in 1897 was named Secretary of the Iowa Conference.[xix]

On March 25, 1900, the General Conference asked Clarence Santee, the president of the Iowa Conference, to assume the presidency of the California Conference.[xx] He traveled to California in June.[xxi] On June 7, Elder WA Hennig was asked to fill the vacant Iowa Conference presidency, but the next day he declined the offer.[xxii] The presidency remained vacant until June 1901, when the Iowa Conference Committee elected LF Starr as its new president.[xxiii] During part of this time, Flora Plummer served as the Acting President of the Iowa Conference.[xxiv]

Someone might claim that Flora Plummer only held this position because Elder Hennig rejected the position and there was no one else to replace him. However, we must remember that the Iowa Conference had 17 ordained pastors at that time.[xxv] Any of them could have easily been elected to occupy that position. The choice of Flora Plummer was therefore due to her ability and natural gifts of leadership. Certainly, she was not the last option.

Flora Plummer’s brief leadership experience seems to have been positive for the Iowa Conference. During that year four new churches were planted and the number of ordained pastors increased to 28.[xxvi] Even the spiritual climate changed for the better. An attendee at the 1901 Iowa Conference session stated that “the business sessions were characterised by unusual quiet and earnestness: there seemed to be a letting go of preconceived opinions, and a settled confidence that One who was able was leading and would continue to do so.”[xxvii]

In May 1901 Flora Plummer was appointed as the new correspondence secretary for the Sabbath School Department of the General Conference, so she left her job at the Iowa Conference.[xxviii] In 1913 she began to lead the Department, which she did until 1936. To date, no other person has broken her tenure record as director of that Department.

Flora Plummer’s leadership shaped the Sabbath School Department into the form we know it today. Her strong and dedicated leadership allowed the Adventist Church to procure thousands of baptisms and millions of dollars in offerings for foreign missionary work.[xxix]

After she died in 1945, Roy A Anderson (1895–1985) declared that “probably no more efficient leadership has been given to any department of our denominational work than that given by our deceased sister to the Sabbath school work during the 36 years of her connection with it.”[xxx]

Petra Tunheim: President of the West Java Mission (1913–1915)

Petra Tunheim was born on February 18, 1871, in the town of Hatteland, Norway.[xxxi] She was the youngest of 10 siblings in a family of farmers and spent most of her childhood “herding sheep and reading her Bible on the lonely hillsides” of her native country.[xxxii] In 1892, after the death of her father, she emigrated to the United States along with her mother and four brothers. There she learned about the Adventist faith and enrolled at Union College, where she also worked as a teacher.[xxxiii]

For a time, she devoted herself to canvassing, until she read in a magazine the need that the church had for missionaries abroad. In 1903 she traveled to Australia, where she worked as a literature evangelist with great success.[xxxiv]

In 1906, during the annual meeting of the Australasian Union, Miss Tunheim offered herself as a volunteer to go to Java as a missionary.[xxxv] Her work initially focused on the city of Surabaya. There a Protestant Dutch woman invited her to go to her mission station. Eventually, she handed over the command of the station to Ms. Petra who took it upon herself to lead and manage it.[xxxvi]

During these years Petra Tunheim sold literature, gave Bible readings, led Sabbath School classes, provided basic medical care, and preached.[xxxvii] In the city of Pangoengsen, she started and led a Sabbath school with about 150 new members.[xxxviii]

Petra Tunhaim also used to travel to rural villages in the area, treating the sick with simple remedies and preaching easy-to-understand biblical themes.[xxxix] Her ministry was not only successful, but she also had the opportunity to witness miracles. For example, the daughter of one of the women who studied the Bible was healed of her illness after Petra Tunheim prayed for her.[xl]

On every mission trip, Miss Tunheim carried a briefcase full of evangelistic literature to sell.[xli] The result was sometimes surprising. A Dutch official received an Adventist tract. He was so interested that he sent letters asking for more material and despite never having met an Adventist in person, he began holding religious meetings on Sabbath with his friends to whom he lent the books that had been sent to him.[xlii]

On another occasion, a Muslim boy named Menan Diredga saw a torn letter written in Malay in the trash can at the home of his Adventist neighbors. Out of curiosity, he stole the remains of the letter and reassembled it to read its content. To his surprise, it turned out to be a letter from Petra Tunheim inviting his neighbors to re-consecrate their lives and prepare for the Second Coming and God’s judgment. Menan could not sleep all night, feeling his complete lack of preparation for the soon arrival of Christ as Judge. The next day he returned to his neighbours’ house, apologised for stealing the letter, and asked for more information about the Second Coming. Soon after, he was able to visit Miss Tunheim, who gave him a Bible in Malay. The young man decided to keep the Sabbath and began to attend Sabbath School.[xliii]

In 1913 the West Java Mission was organised, and Petra Tunheim was named its president and treasurer.[xliv] The center of its activity was in the city of Batavia. The Seventh-day Adventist Church differentiates a “mission” from a “conference” by its self-sustaining capacity and missionary needs, among other factors. However, the president of a mission and a conference essentially share the same responsibilities and have the same authority over their respective territory.

During these years of work, Miss Tunheim suffered several times from severe tropical diseases, such as malaria. However, she fulfilled her administrative and ecclesiastical duties even when she was ill.[xlv] In 1915 her health deteriorated so much that she had to return to the United States to restore her physical condition.[xlvi] A year later she returned to Java to resume her evangelistic work, but in 1919 she again had to leave after being attacked by the disease; this time she went to Shanghai.[xlvii]

At the Sanitarium of Shanghai, she began to learn Mandarin Chinese. This was her seventh language. In addition to Norwegian, her mother tongue, she spoke English, Dutch, Malay, Javanese, and Cantonese Chinese. In a matter of a few months, she was giving Bible studies in Mandarin Chinese.[xlviii]

In Shanghai, she was diagnosed with cancer. WH Miller, the director of the Sanitarium, offered to keep her as a patient for as long as she lived. She refused. Instead, she wanted to go back to Java and spend her last days preaching to her Malay friends. Unfortunately, her health was quite poor and she died en route on the ship taking her from Singapore to Batavia.[xlix]

The Australasian Record published an obituary titled “A Modern Heroine”:

“This heroine, whose Christian life and works compare well with the most famous records of mission annals, visited four continents, made nine long sea voyages, learned seven languages! Her influence was always for the right, witnessing for the truth she believed; her prayers were unmistakably earnest; her testimonies were constantly ringing with the inspiration of soul-saving effort.”[l]

After her death, the new president of the West Java Mission decided to finish the construction of the Batavia temple as a memorial for Miss Tunhaim, who had started it 10 years earlier. The inhabitants of the city of Batavia not only donated high-quality materials but also sent workers to build the church, as a “token of their affection for her”. Once completed, the church could seat 500 people.[li]

Charles H Watson, president of the General Conference from 1930 to 1936, wrote: “I visited Singapore many times, and always I made a pilgrimage to Miss Tunheim’s grave. I used to feel I was looking at the resting place of a saint.”[lii]

Phyllis Mosley Ware: President of the Central States Conference (1994)

On the first day of the 2005 General Conference Session, held in St. Louis, Missouri, a woman came to the front, took the microphone, and delivered the opening prayer for a meeting that gathers leaders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church from all around the world. That woman’s name is Phyllis Mosley Ware.[liii]

Jan Paulson, by then president of the General Conference, described her as an individual that “served the church in such an outstanding manner” and “represent[ed] leadership and ministry of the kind that are models for many of us to emulate”.[liv]

Phyllis Mosley was born in Kansas City, Missouri. She studied at the University of Notre Dame majoring in business with one of the highest grade point averages in her class. In 1975 she was baptised in the Linwood Adventist Church. After her graduation, she hoped to work as an accountant for the Church but no positions were available.[lv] During the following years, she worked in some private companies, until in 1983 she was invited to work in the Central States Conference.[lvi] She began as Chief Accountant, but eventually was promoted to Assistant Treasurer, and then Treasurer (1988–2008) and Executive Secretary (1988–2004).

Beginning in 1984, she became a worker for the Adventist Church and received a missionary license. From 1990 to 2008 she received a license as a commissioned minister, and this is recorded in the Yearbooks of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.[lvii] Although her studies and profession lean toward business and finances, she had remarkable spiritual ability. She was described as a woman with “beautiful Christian manner[s]” who “has no difficulty getting everyone enthusiastically involved in Bible studies”.[lviii] James Cress (1959–2009), who served as Secretary of the Ministerial Association of the General Conference from 1992 to 2009, included Phyllis Ware in a list of “women who have impacted my ministry”.[lix]

On February 22, 1994, John Paul Monk Jr, president of the Central States Conference, passed away after a long and hard struggle with cancer.[lx] Since the position of president had become vacant, Phyllis Mosley Ware was asked to serve as the Conference’s Acting President until a permanent replacement could be found.[lxi] She was serving as Treasurer and Executive Secretary at the time, adding to these responsibilities the position of President. Although her tenure as Acting President was officially only a few months long, she had been carrying out many presidential duties after Elder Monk was diagnosed with cancer in 1989. Phyllis Ware was his “right hand” and, as the disease worsened, she started to help him more and more to conduct conference business.[lxii] To the best of the author’s knowledge, Phyllis Ware has been the only Adventist administrator of either sex to hold the top three positions in a Conference simultaneously.

While it is true that Phyllis Ware became president of the Central States Conference due to an unexpected tragedy, she was certainly not the only option available to fill the vacancy. The Conference Executive Committee had six ordained pastors who might as well have held that position.[lxiii] However, she was the one chosen to fill the vacancy, undoubtedly due to her remarkable leadership skills. As a result of this event, in 1999 the Association of Adventist Women awarded her a special recognition: the “Outstanding Achievement Award”.[lxiv]

Phyllis Mosley Ware worked for the Central States Conference until 2008.[lxv]

Final Thoughts

On October 27, 2013, the Southeastern California Conference elected Sandra Roberts as its President. This election was marked by controversy, as it was claimed that the Conference proceeded against the Working Policy of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which requires presidents to be ordained pastors, but at the same time prevents the ordination of women pastors.[lxvi] It is not the purpose of this article to question or defend the legitimacy of this election. This short article is historical in nature and only seeks to fill a gap in the study of female participation in church leadership in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. However, it is necessary to make a clarification regarding this election. Some journalists described it as revolutionary or novel, claiming, for example, that “a woman has been named president of a Seventh-day Adventist conference for the first time in the denomination’s 150-year history” (emphasis added).[lxvii] But statements like these are clearly wrong. Flora Plummer, Petra Tunheim, and Phyllis Ware were Conference Presidents decades before Sandra Roberts was elected. The Adventist Church already had a precedent of appointing women as Conference leaders.

Finally, it remains to be asked: Were Flora Plummer, Petra Tunheim, and Phyllis Ware the only women to serve as Conference Presidents? It is the author’s firm conviction that the lives and works of other women who also served in this position remain to be discovered. As historical research digs deeper and broadens our knowledge of the Adventist Church’s past, wonderful new stories will emerge of people who with dedication and effort led in the least thought of positions and places.

Eric E Richter, School of Theology, River Plate Adventist University, Argentina.