What was the identity of the man whom the robbers stripped of his clothes, “beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead” (Luke 10:30)?

Was he rich or poor? We don’t know. Was he black, white, tan or brindle? Jesus doesn’t say. Was he a Jew, a Gentile or of mixed race? We’re not told. Was he a person with status and learning or of no significance? Again we have no idea. Indeed, we know nothing of him other than the detail that he was travelling from Jerusalem to Jericho when he was assaulted and robbed. Yet despite our ignorance of him, in many ways, he’s the central figure in Jesus’ well-known story, traditionally called “The Parable of the Good Samaritan” (Luke 10:25–37).

This deservedly famous story is set within a debate between Jesus and a lay expert in the interpretation of the Law of Moses, concerning the meaning of Leviticus 19:18. The exchange progresses through two sets—each made up of a pair of questions with a pair of answers.

Set one

Expert’s first question: “What must I do (poiein) to inherit eternal life” (v 25)? This was a somewhat common question. Luke makes it clear that the expert asks his question to test the learning of the provincial Galilean Sage, but Jesus deflects the trap by asking a return question.

Jesus’ first question: “What is written in the Law? What do you read there” (v 26)? The expert is obliged to answer, since he is the acknowledged authority in interpreting the Law of Moses. He would lose face with the onlookers if he made an attempt to turn his question back onto Jesus.

Expert’s first answer: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbour as yourself” (v 27). His answer quotes two central passages in Judaism—Deuteronomy 6:5 (compare 10:12; 13:3; 30:6) and Leviticus 19:18—so the expert is staying close to his Jewish interpretative tradition.

Jesus’ first answer: “You have given the right answer; do (poiein) this, and you will live” (v 28). Jesus has given an unequivocal answer: what must the expert do to attain eternal life? He must do the essence of the Mosaic Law, that is, to love God totally and his neighbour as though loving himself.

Set two

Expert’s second question: “And who is neighbour of me (mou)?” (v 29 author’s literal translation; “of me” can mean “to me”)? By responding with a question, Jesus forces the expert to ask it himself as a genuine inquiry. The expert needs to do this to defend his reputation before the bystanders for having asked such a simple query about the Law that he himself was able quickly to resolve. But why ask it at all?

The answer becomes apparent when the text is read in full as it occurs in the Law: “You shall not hate in your heart anyone of your kin; you shall reprove your neighbour, or you will incur guilt yourself. You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Leviticus 19:17,18, italics added). In context the command to “love your neighbour as yourself” is restricted to fellow Israelites. KKK leader Chris Barker appealed to this context to refute Ilia Calderón, an Afro-Latina TV journalist: “No! Wrong! Leviticus 19:18 says ‘Love the neighbour of thy people.’ My people are white. Your people are black” (interview, August 2017).

Jesus again responds to the expert’s question with His own question, but before asking it He primes the pump with the story of the amazingly generous Samaritan. The Samaritans were rival claimants to being the people of God. Their priesthood, their temple, their mountain, their city and their version of the Law were true worship. As a result of such unrestrained rivalry, the Jews and the Samaritans hated each other intensely.

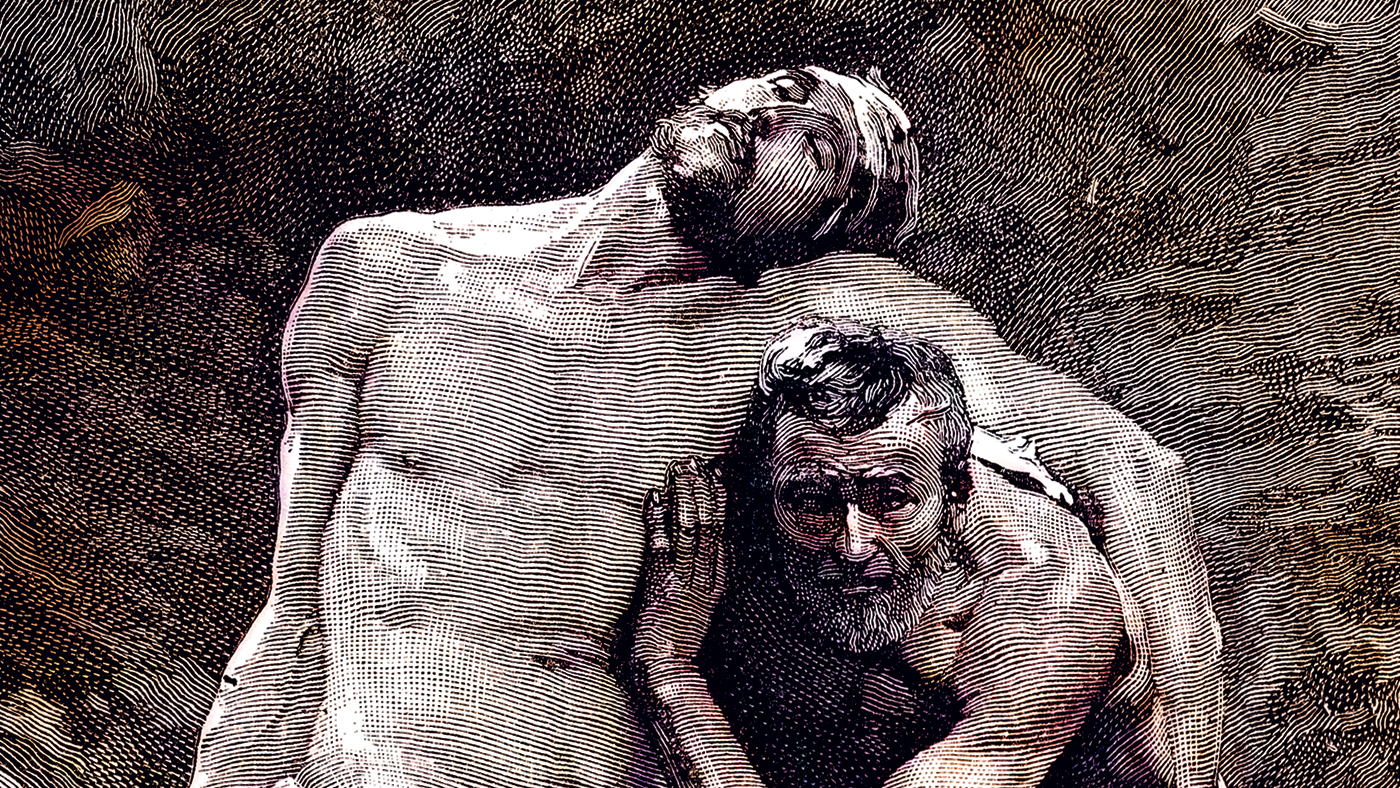

Why did the priest and the Levite pass by the wounded traveller at the roadside? Was it because they assumed the assaulted victim was not a Jew, and therefore not their neighbour? The Samaritan’s kindness to the battered stranger is staggering in its generosity (vv 34,35). He personally tends his wounds, transports him on his own animal to a hostel and pays all costs—and this to an unknown stranger. Jesus’ parable dictates the answer to His next question.

Jesus’ second question: “Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbour to the man who fell [literally, “of the man who fell”] into the hands of the robbers” (v 36)? This of course is not the same as the expert’s second question (v 29). The expert asked: “Who among my kinsmen qualifies as my neighbour?” His concern focuses on who’s in and who’s out; who qualifies to receive his largess and who doesn’t. Jewish prostitutes, who service the hated Roman occupation auxiliary troops, are out. Equally excluded are the Jews who collect the Roman taxes. Those of mixed-race, such as the Samaritans, are hardly kinsmen, so they are not “neighbour” for any orthodox Jew. [pullquote]

The expert’s question: “who is neighbour of me?” meant for him, “To whom should I show love?” But it could also mean “who showed love to me?” The last is how Jesus understood it, which compels the expert to identify with a half-dead stranger by the roadside. The parable of the Samaritan permits only one answer to Jesus’ second question, and the expert knows he cannot avoid giving it.

Expert’s second answer: “The one who acted (poiein) mercifully to him” (v 37a author’s translation); and that one was a detested Samaritan. The expert must have choked on that reply, especially as Jesus had forced him to identify with the wounded stranger by the roadside.

Jesus’ second answer: “Go and do (poiein) likewise.” The expert’s initial question (“what must I do?”) has now been definitively answered: “practise (poiein) mercy as the Samaritan did, and you will receive eternal life.”

In the first set, “neighbour” refers to the extent of the object who receives one’s love, but in the second set the parable forces the expert, as Jesus intended, to apply it to the subject who provides the love. In this way Jesus universalises the law of Leviticus 19:18, that is, He transforms a nationally specific law into a universal and unrestricted spirit of love, one that denounces the KKK’s interpretation of Leviticus 19:18 as anti-Christ.

The crucial nature of Jesus not stating the identity of the victim is now apparent: He defines “neighbour” not by the identity of the recipient (as in the Law), but by the benefactor’s merciful action. Hence the twofold use of the verb “to do” at the beginning of the story (vv 25,28) and again at its end (v 37). So it’s not externals like colour, race, creed, culture or gender that define “neighbour” but the doing of indiscriminate acts of mercy and love.1

Since it’s what we do and not the identity of the recipient that defines “neighbour”, why identify the benefactor as a Samaritan? Because his surrounding culture automatically classified him derogatively as a despised foreign opponent. Yet, surprisingly—and this is the genius of the story—against all expectations, his generous and merciful behaviour demonstrated that he acted as the neighbour to the man who fell among the thieves and not the priest or the Levite. “Go thou and do likewise.”

Dr Norman Young is a former senior lecturer at Avondale College of Higher Education.