One of the things I love to do the most in my own personal study of Scripture is to really dig down deep into the meaning of words. I don’t just mean to look at the original language, search up the meaning in a concordance or lexicon, or even to consider the grammatical context of its use in a particular passage. We can get so much more depth of insight and understanding when we understand the historical use and context of a word as it was used and understood when it was written.

Too often words we use change meaning over time and use. Good examples of this are English words like the word “awful”. If I used this word today, I would be describing something as being horrible, terrible or unpleasant. However if you got in a time machine and went back 400 years, you would find it was used in a completely different way. It would have been used to describe something that literally was “full of awe” or wonder. If you stood and saw an amazingly spectacular sunset, it would be accurate to say it was awful (full of awe).

If one English word can change in use and meaning so much in just over 400 years, then clearly there is work to be done. Like a good archaeologist, we take the words used in the Bible and dig down; removing layer after layer of meaning until we discover the meaning which was relevant at the time the Bible was written so as to properly discern what the Bible writers meant when using certain words.

One such word that has been covered over with layers of various meaning in the past 2000 years is the word “church”. Many of us are already aware that most people think of this word as referring to a building or an organisation and that this is a long way from what the original Greek word used actually meant.

The Greek word translated as church is ekklesia and, as many have rightly pointed out, in its simplest meaning the word refers to “an assembly of people for a purpose”. Hence you may have heard it said that the church is not the building but the people.

Many will be unaware however that there is another layer of meaning connected to the cultural context of Jesus’ day that adds significance to Jesus’ choice to use this word.

The first point to make is that although we know Jesus likely spoke Aramaic daily, he probably would have had a good understanding of Koine Greek, the common language of the Roman empire. The reason for this is twofold. Firstly, because we know it was widely spoken through the Roman empire, so much so, this was the language of choice used by the writers of the New Testament. Secondly, Jesus spent some of his time growing up in Egypt, likely Alexandria where there was a large diaspora of Jewish people, who were predominately Greek in language and culture.

What makes Jesus’ use of this word so important to spend time considering? Because in all of the Gospel accounts, Jesus only uses this word twice (Matthew 16:18 and 18:17). Both times He uses it in a specific context.

When Jesus speaks of the community He has come to establish in the Gospels, He overwhelming uses the term “the kingdom” (more than 100 times) but only the word church twice. So why? I remember researching the earliest use of the word ekklesia in Greek culture, which culminated in an amazing discovery when I visited Athens on a Bible lands tour in 2019.

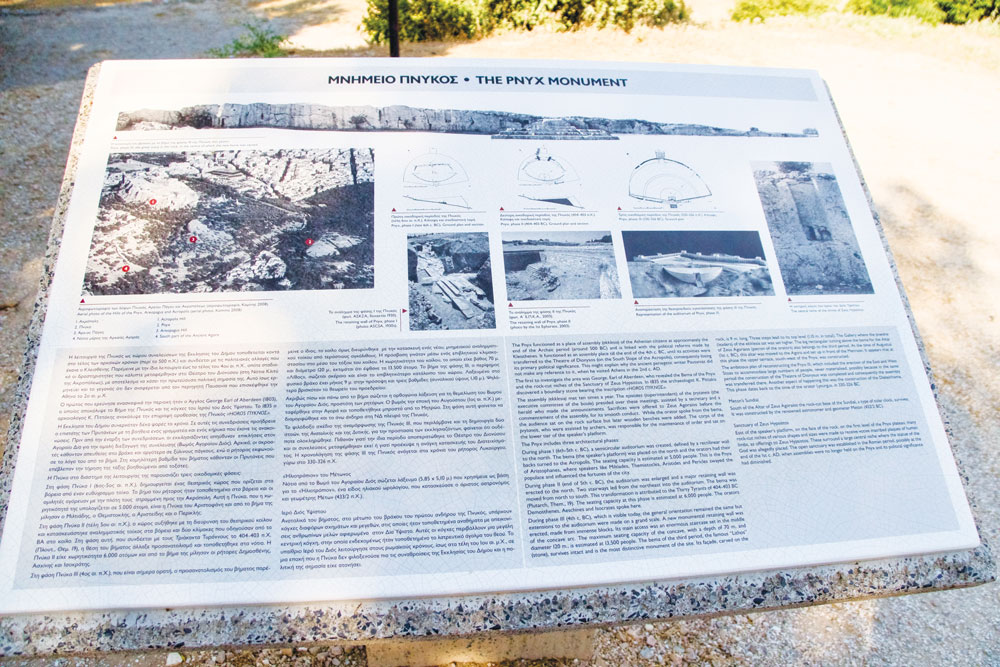

For most Bible scholars, bucket list sites to visit in Athens are the Acropolis and Mars Hill, but I was most interested in visiting another site on the same famous ridge line. During my free time, I went in search of the Pnyx, just a few hundred metres past Mars Hill. This is the site of the home of democracy. When the city state of Athens became a democracy, it operated differently to how most modern democracies work. Whenever an important decision needed to be made for Athens, including things such as whether to go to war, appointing officials, approving legislation or trying political crimes, they didn’t call on representatives as we do today. Rather, every male over the age of 20 who was a citizen had the right to attend an assembly at the Pnyx, where they directly voted on such matters. Attendance was not compulsory, however there was a quorum required for decisions to be made, usually around 6000.

The Pnyx is a large flat area cut out of the hill face where the citizens of Athens would gather. When I visited the site I discovered a couple of interesting facts. Firstly, as seen in the sign pictured, the official name of the gathering of the citizens for these official assemblies was (you guessed it) ekklesia. This would likely be a common association people would have with this word when it was used in Jesus’ day; the idea of a gathering of citizens for the purpose of making important decisions about the kingdom. Secondly, the chairperson of the assemblies did not have any authority other than to maintain correct order of these assemblies and he would always stand on an elevated platform called a bema which indicated his authority. This bema could be built out of any material. However at the Pnyx, the bema is cut and hewn out of the bedrock of the hillside. Notice now the specific contexts in which Jesus then used this word in speaking to His disciples.

“’I also say to you that you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build My church; and the gates of Hades will not overpower it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; and whatever you bind on earth shall have been bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall have been loosed in heaven’” (Matthew 16:18,19, NASB95, emphasis added).

“’If your brother sins, go and show him his fault in private; . . . If he refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if he refuses to listen even to the church, let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector. Truly I say to you, whatever you bind on earth shall have been bound in heaven; and whatever you loose on earth shall have been loosed in heaven. Again I say to you, that if two of you agree on earth about anything that they may ask, it shall be done for them by My Father who is in heaven. For where two or three have gathered together in My name, I am there in their midst’” (Matthew 18:15–20, NASB95)

Notice in both passages, Jesus is speaking about the disciples acting in authority regarding God’s kingdom purposes here on earth. Also notice in the Matthew 18 passage, Jesus tells us the quorum of the assemblies for Jesus followers, “where two or three are gathered in My name”.

When we understand this context, it adds important meaning to Jesus’ deliberate use of the word ekklesia. He was communicating to us that something more significant is happening when we gather together other than just enjoying fellowship and worship. Rather, He is saying that as we gather, He has given authority to His people to lock or unlock the purposes of God’s kingdom here on earth. Also, Peter is not being pictured here as the one who makes the decisions. Rather, the language paints him as the chairperson who maintains order of the assembly. However, it is in the agreement of the body of all believers where the authority lies.

This begs the question: if we properly understood why Jesus uses the word ekklesia in the fullness of its historical context, how does this change our understanding about an important and possibly forgotten role of the assembling of God’s people together? What matters of God’s kingdom should we be locking and unlocking when we gather? How can we claim the great privilege of being God’s kingdom citizens on Earth?

May we truly rediscover the full significance of being God’s ekklesia on Earth so we may see His “kingdom come. [His] will be done, On earth as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10, NASB95).

Matthew Hunter is the pastor at College Park and Birdwood churches in South Australia.