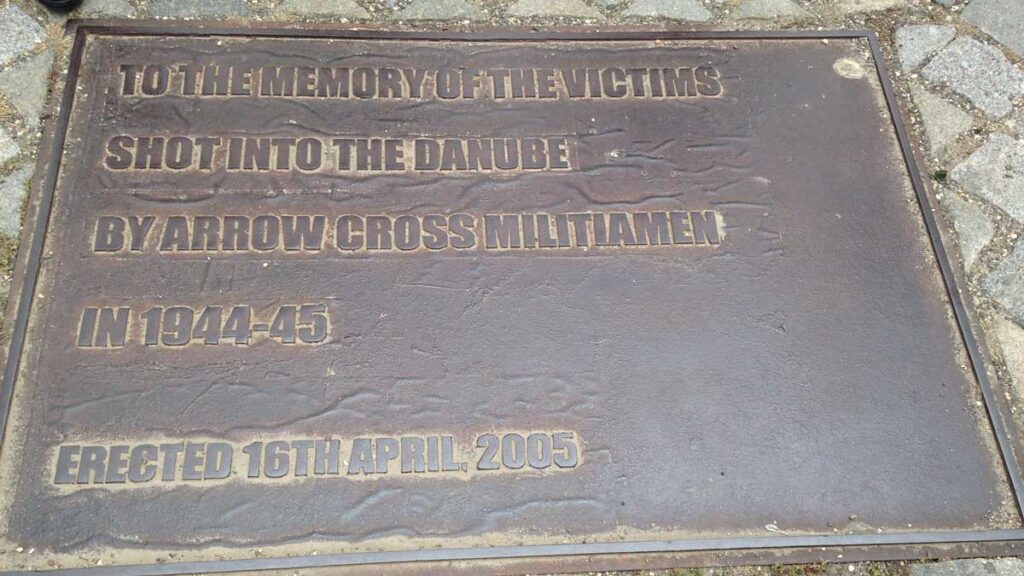

It was an intriguing piece of artwork; a row of cast-iron shoes of various kinds and sizes that sat on top of a ledge running parallel with the bank of the river Danube in Budapest. Curious, my wife and I paused to examine the sculptures more closely. A plaque informed us that the display commemorated “the memory of the victims shot into the Danube by Arrow Cross Militiamen in 1944–45”. What the memorial plaque neglected to tell us was that the victims were all Jews—men, women and children. It also overlooked to inform us that the Arrow Cross was the viscous equivalent in Hungary of the German Nazis and that it was a more brutal group than they were.

The holocaust would have to be the worst example of a ruthlessly perpetuated genocide in all of human history. Six million Jews, two-thirds of their European number, were exterminated. They were starved, shot, worked to death, diseased, killed in medical experiments, and gassed. Few nations can review their reaction to this insane horror without shame.1

Could the Holocaust (Shoah) have been prevented?

Saul (also Paul) was not so much converted when Jesus confronted him on the road to Damascus, but called to be an apostle to the Gentiles and to the Jews. Jesus chose him to bring His “name before gentiles and kings and before the people of Israel” (Acts 9:15). Paul was obedient to this “heavenly vision” (Acts 26:19) and began immediately to teach in the synagogues (Acts 9:20) to the Jews first but also to the Greeks (Romans 1:16; Acts 19:10).

Among those who were attracted to the apostolic witness to Jesus in the synagogues beyond Palestine were Jews and Gentiles/Greeks (Acts 13:48; 14:1; 18:4; 19:10); former Gentiles (proselytes); Gentiles who feared God (Acts 10:2, 22, 35; 13:16, 26) and Gentiles who worshipped God (Acts 13:43, 50; 16:14; 17:4,17; 18:7). All these groups included both men and women (Acts 13:50; 16:13,14; 17:4,12; 22:4). Consequently it is safe to conclude that all Paul’s Jewish converts and a large portion of the Gentiles that accepted his message had the prior practice of attending the synagogues on the Sabbath. The ethnic diversity of Paul’s missionary success in the synagogues is reflected in the membership of his assemblies: Jew and Greek (Romans 1:16; 2:9, 10; 3:9; 10:12; 1 Corinthians 10:32; 12:13; Galatians 3:28; Colossians 3:11); circumcised and uncircumcised (Romans 3:30; 4:9, 11; 1 Corinthians 7:18; Galatians 2:7; Colossians 3:11); Jew/circumcised and (Romans 3:29; 9:24; 15:8,9; Galatians 2:14); slave and free (1 Corinthians 7:22; 12:13; Galatians 3:28; Ephesians 6:8; Colossians 3:11); weak and strong (Romans 14:1; 15:1); male and female (Galatians 3:28); barbarian and Scythian (Colossians 3:11).

The word ekklˉesia, which Paul uses 62 times, means an assembly, a gathering together; it does not mean church as a building or an administrative structure. The early believers, Jew and Gentile, gathered together as an assembly (1 Corinthians 11:17), that is, in the same location and at the same time. Paul speaks of the whole assembly coming together (1 Corinthians 14:23a). The language of assembling together is frequent “when you come together as a church [assembly]” (1 Corinthians 11:18) and elsewhere (Acts 15:30; 1 Corinthians 11:17, 20, 33, 34; 14:26).

The question might now be asked: “When would such a mixed assembly of Jews and Gentiles—both of whom to a large degree had attended synagogues on the Sabbath—gather together in the name of Jesus? The only feasible reply is “on the Seventh-day Sabbath”. Then why does Paul never quote the fourth commandment? For the same reason that he never cites the first, second or third commandments, that is, they were so well known and so widely practised that they were assumed: One God (Romans 3.30; 1 Corinthians 8:4; Ephesians 4:6), no idols (1 Corinthians 10:14; 2 Corinthians 6:16); reverence for God (Matthew 6:9; Luke 11:2; 2 Timothy 2:19); Sabbath (mentioned 71 times in the NT without any indication of its cessation). Some will object and refer to Romans 14:5; Galatians 4:10; Colossians 2:16.

A translation closer to the Greek text of Romans 14:5 gives a very different perspective: “On the one hand, one person regards a day above a day, but on the other hand another person regards every day.” The phrase “every day” implies a group of days; it certainly cannot mean “no day”. In the congregations in Rome there were those who perceived that the Jewish food laws were no longer mandatory (that is, “the strong”, who ate anything, v2a) while others thought they were still obligatory (“the weak”, who abstained from meat and wine in case some of the food on the table was “unclean” or perhaps had been offered to idols (vv 2b, 21). The context was communal meals where the participants included Jewish and Gentile believers. The issue in the Roman assemblies was whether the Levitical food laws regarding “clean” and “unclean” still applied in the era of Christ (vv 14,15,17,20,21).

The matter of the days would also be Jewish festive days, where the “strong” preferred some days (likely Passover and Pentecost) while the “weak” esteemed them all. Paul’s concern for the congregation was not what food or which festive day, but that when they gathered together—Jewish and Gentile believers—they did so in a spirit of brotherly and sisterly love (vv Romans 14:10,13,15,19; 15:2,5,6). The word “Sabbath” is not mentioned in the passage and nor is it implied.

The list in Galatians 4:10 (“You are observing special days and months and seasons and years”) sums up the annual calendar of the Mosaic temple. However, Paul speaks of the Galatians turning “back again to the weak and beggarly elemental principles?” Paul warns the Galatians that if they abandon Christ for the rituals of the Jewish temple, they might as well return to the rituals of their former pagan temple, as it too was ordered by “days, months, seasons and years”. If the “days” in this list is the Sabbath, it is there as part of the temple ritual and not as the day of gathered worship in a synagogue or an assembly.

Likewise the list in Colossians 2:16 (“Therefore, do not let anyone judge you regarding food and drink or with respect to festival, new moon, or Sabbath”, author’s translation) is a formulaic reference to the OT’s festival days. The three terms summarise the time-sequences in the Jewish ritual calendar of the sanctuary (1 Chronicles 23:31; 2 Chronicles 2:4; 8:13; Nehemiah 10:33) and as such they refer to grain, burnt and sacrificial offerings and not to gathered worship in a synagogue, a hall or a home.

An orthodox Jew would have no problem with Gentiles assembling on temple-days, but uncircumcised Gentile and circumcised Jewish believers gathering together for communal meals would be unacceptable (Acts 10:28; 11:2,3; Galatians 2:12,13). It is not the festive days per se that are judged, but rather the manner in which the assembled Jewish and Gentile believers celebrated them in communal worship.

In turning to the Gospels it should be remembered that they post-date Paul’s letters. Hence they reflect the interests of the communities for whom they were written. This is widely recognised today. To quote Daniel J Harrington (Catholic): “They were expressed in such a way as not only to describe Jesus in his original setting but also to address the problems facing the Christian communities of a later time.”2

Six of Jesus’ Sabbath healings involved chronic conditions, thereby indicating that acts of compassion were compatible with it and therefore brooked no delay (Mark 1:21–28; Luke 4:31–37; Matthew 12:9–14; Mark 3:1–6; Luke 6: 6–11; Luke 14:1–6; John 5:1–15; 7:21–24; John 9:1–34). Thus Jesus made it plain that it was consistent with the Sabbath to do good, to heal, to save life, and to free those bound by the Evil One (Mark 3:4; Matthew 12:12; Luke 6:9; 13:16). Several of Jesus’ sayings affirm the Sabbath: “The Sabbath was made for humankind and not humankind for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27), or “For the Son of Man is lord of the Sabbath” (Mark 2:28; Matthew 12:8). Why would the Gospel author remember these sayings, if in his day the Sabbath was no longer observed? Members of the early Christian assemblies would read these healings and sayings of Jesus not as addressing whether to honour the Sabbath but how to. As James Dunn (Church of Scotland) notes: “The question under debate is not whether the Sabbath should be observed, but how it should be observed.”3

The resurrection is supposedly the event that facilitated the change to Sunday, yet the Gospels give the date in the Jewish manner. “And very early on the first day after the Sabbath (sabbat¯on) the sun having arisen, they went to the tomb” (Mark 16:2, author’s translation. See also Matthew 28:1; Luke 24:1; John 20:1,19). The NT consistently uses the Jewish manner of dating the day: “On the first day after the Sabbath (sabbat¯on) when we gathered together to break bread . . .” (Acts 20:7 author’s translation); “On every first day after the Sabbath (sabbatou), let each of you set aside at home . . .” (1 Corinthians 16:2 author’s translation).

The constant reference to the Sabbath without any comment regarding a transition to Sunday as the day of gathered worship in the apostolic age is inexplicable. No mention is made of Sunday when referring to the Lordship of Jesus over the Sabbath (Mark 2:28), or to His and Paul’s pattern of synagogue attendance on the Sabbath (Mark 1:21; Luke 4:16; Acts 17:2), or to the women’s observance of the fourth commandment (Luke 23:56), or to their returning to the tomb “the Sabbath having passed” (Mark 16:1), or to the resurrection of Jesus occurring “after the Sabbath as it was dawning towards the first day after the Sabbath” (Matthew 28:1, author’s translation), or to the undesirability of fleeing Jerusalem on the Sabbath (Matthew 24:20), or to the preparation day prior to the Sabbath (Mark 15:42; Matthew 27:62; Luke 23:54; John 19:31,42). If at the time of the composing of the Gospels the Sabbath had been abandoned, it is very improbable indeed that the writers would mention it so frequently without explaining that Sunday was now the new day of worship. If Jesus’ resurrection was the basis for the switch to Sunday, it is extremely strange that all the Gospels consistently refer to it as occurring on “the first day after the Sabbath” without further clarification.

So, could the Holocaust (Shoah) have been prevented?

Yes, provided the ethnic and social diversity within the Pauline assemblies had been maintained. They gathered together as one body with many parts: “For in the one Spirit we were all baptised into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free” (1 Corinthians 12:13). “In whatever condition you were called [circumcised or uncircumcised, slave or free], brothers and sisters, there remain with God” (1 Corinthians 7:24). Therefore, Paul’s vision for the Sabbath went beyond gathering together on the seventh-day; it also demanded the practice of a diverse and inclusive assembly (including the poor and unbelievers, 1 Corinthians 1:26–29; 14:22–24).

The second-century change to Sunday forced the Jews out of the assemblies, which plunged Christianity into the anti-Semitism that has blighted it ever since. Failing to retain the inclusive and diverse nature of Paul’s assemblies tears the heart out of the Sabbath. Thus, how the Sabbath is celebrated is as important as, or even more important than, when it is celebrated.

- In the summer of 1938, 32 significant nations met in Évian (France) to discuss raising their limit of refugees they would accept, in order to help more Jews escape from Nazi Germany’s persecution. Only the tiny Dominican Republic chose to do so. The Australian delegate, Colonel TW White, declared: “as we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one by encouraging any scheme of large-scale foreign migration”.

- “The Jewishness of Jesus: Facing Some Problems,” in James H Charleswoth (ed), Jesus’ Jewishness: Exploring the Place of Jesus in Early Judaism (New York: Crossroad, 1991) 131–132.

- Jesus Remembered (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), volume I.568–569.

Dr Norman Young lectured at Avondale College (now University) for 31 years (1973-2004). In retirement, he still enjoys studying and publishing the occasional article.